Before diving into the different Incident Response (IR) models, we first need to define what an incident actually is.

According to Wikipedia:

“An incident is an event that could lead to loss of, or disruption to, an organization's operations, services, or functions.”

By this definition, an incident is essentially any event that negatively impacts business operations. It could be a ransomware attack, a system failure, or even a power outage that halts production lines.

In the digital realm, the scale of incidents is staggering: there are an estimated 600 million cyberattacks per day, and about 54 victims (people) every second. These numbers highlight the urgent need for organizations to strengthen their defenses.

When we talk about responding to incidents, we mean all the efforts taken to block, stop, and contain the incident, while at the same time trying to maintain or restore normal business activities as quickly as possible.

With this understanding, we can now clearly define Incident Response (IR) as the structured process of managing and mitigating the impact of incidents.

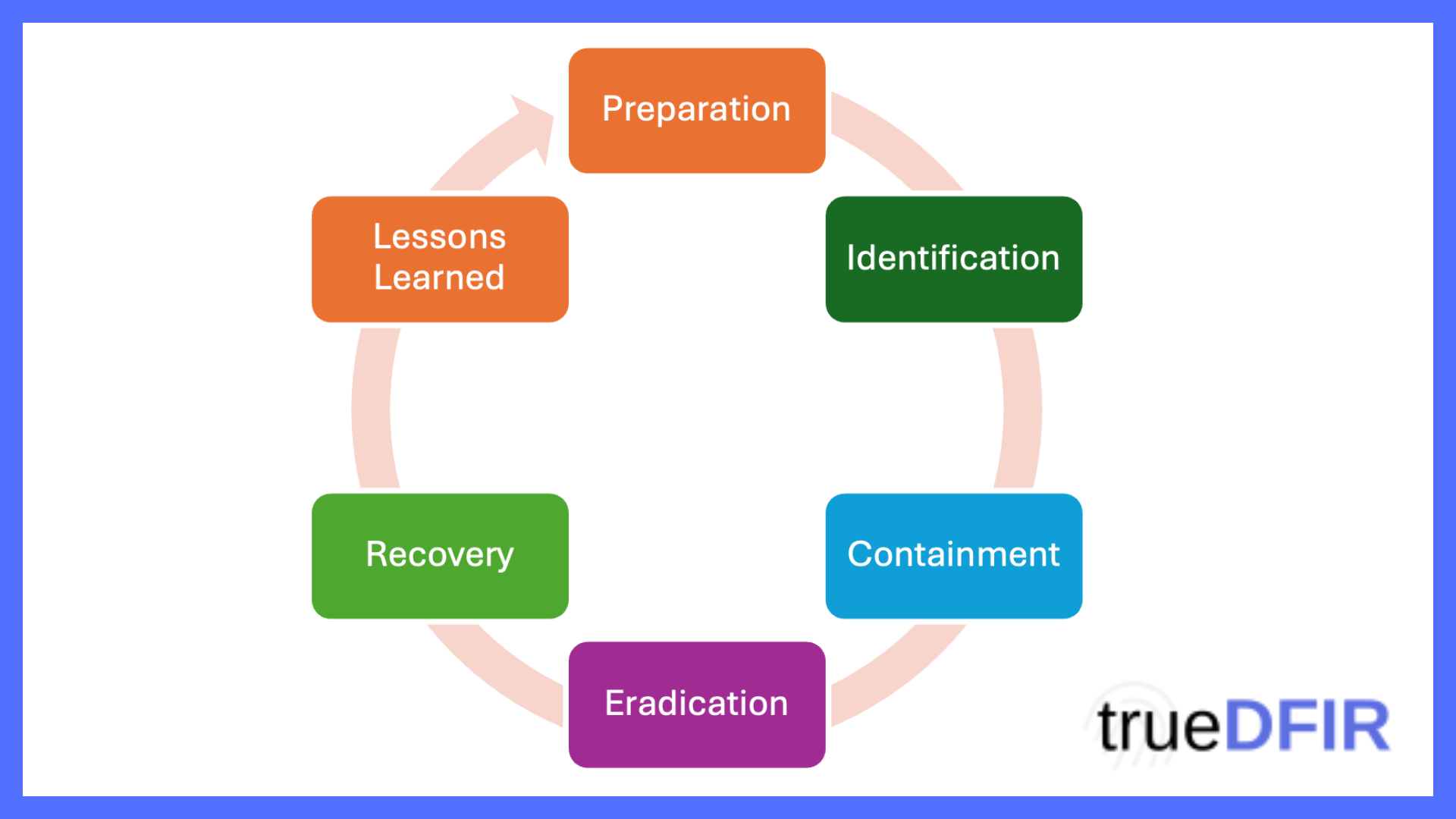

An IR model provides a framework for this process. It consists of specific steps or phases that guide how to respond to an incident. Typically, IR models follow a chronological order—meaning you must complete step 1 before moving to step 2, and each step influences the next. However, there are exceptions, such as the Dynamic Approach to Incident Response, where steps can overlap or be revisited depending on the situation.

PICERL Model

One of the most widely recognized approaches to incident response is a six-phase model originally developed within U.S. government agencies and later formalized by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). With a long track record of effectiveness, it serves as a strong foundation for organizations aiming to structure their response and recovery strategies.

The six phases are: Preparation, Detection & Analysis, Containment, Eradication, Recovery, and Post-Incident Review.

1. Preparation

The cornerstone of incident response is readiness. This phase is about more than just having a response team on standby—it focuses equally on prevention. Ensuring that infrastructure, networks, and applications are hardened and security controls are in place reduces the likelihood and impact of incidents.

2. Detection & Analysis

The response process begins when something suspicious is noticed. This might come from a security alert, a user report to the help desk, or proactive threat hunting. Analysts validate the event, confirm whether it qualifies as a true incident, and assess its potential severity. Once confirmed, the investigation expands to determine scope and impact.

3. Containment & Threat Intelligence

At this stage, the objective shifts to limiting the attacker’s ability to cause further harm while gathering intelligence about the adversary’s tactics. Responders focus on identifying the entry point, persistence mechanisms, methods of lateral movement, and command-and-control infrastructure. Simultaneously, security visibility is improved across affected hosts and networks. This phase not only mitigates damage but also produces valuable threat intelligence that can inform both defensive improvements and future investigations.

4. Eradication and Remediation

This stage is often considered the most critical in the response lifecycle. The objective is to completely eliminate the threat and return systems to a stable state. However, eradication must only begin once the full scope of the compromise has been identified. Acting too quickly without full visibility frequently results in reinfection or overlooked persistence mechanisms.

A structured remediation plan is created and executed carefully to ensure stability. Typical activities in this phase may include:

- Blocking known malicious IP ranges

- Sinkholing or disabling harmful domains

- Reimaging or rebuilding affected machines

- Coordinating with external service or cloud providers

- Enforcing enterprise-wide password resets

- Validating that applied fixes are effective and sustainable

5. Recovery

The recovery phase is about bringing the organization back to business as usual while ensuring that security posture is strengthened. By this point, the investigation has revealed valuable insights, and these should guide improvements to prevent recurrence. Recovery efforts are generally broken down into short-term fixes, medium-term adjustments, and long-term security initiatives.

Examples of recovery actions include:

- Improving identity and access management across the enterprise

- Expanding network monitoring and visibility

- Rolling out a structured patch management process

- Formalizing a change management program

- Centralizing log collection and analysis (via SIEM)

- Enhancing password management systems

- Launching or expanding user awareness and training campaigns

- Redesigning parts of the network to reduce attack surface

6. Lessons Learned & Continuous Improvement

The final phase ensures the incident has been fully contained and neutralized, and that defenses are truly stronger than before. This involves validation through additional monitoring, targeted sweeps to detect lingering traces of compromise, and security assessments such as penetration testing or compliance audits.

Equally important, this step transforms the incident into a learning opportunity. The organization documents what worked, what failed, and what must change. The result is a more resilient security program and a response team that is better prepared for the next incident.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *